Why is your computing environment important?

Edit this Page via GitHub Comment by Filing an Issue Have Questions? Ask them here.In this page, we talk about reproducible best practices to use software on the FH cluster (rhino / gizmo). If you’re getting started on rhino / gizmo, this page is for you.

Learning Objectives

After reading this page, you will be able to

- Describe what the dependency nightmare is for software

- Utilize software environment modules on

rhino/gizmoand integrate them into your scripts - Utilize Docker containers and integrate them into your scripts

- Utilize

condato install software onrhino/gizmoto your home directory - Discuss Why compiling software is difficult and who to talk to

- Describe first steps to reproducible computing with easymodules

- Discuss how to transform a snakemake script to Workflow Description Language (WDL).

Why can’t I just install software on rhino/ gizmo like my laptop?

The FH computational cluster is a shared resource. It needs to be maintained and work for a variety of users. Giving individual users root access is not advisable because it is a shared resource.

The Dependency Nightmare

| Source: [The b(ack)log | A nice picture of (dependency) hell (thebacklog.net)](https://www.thebacklog.net/2011/04/04/a-nice-picture-of-dependency-hell/) |

Motivation: avoid dependency hell. Often, different software executables are dependent on different versions of software packages (for example, one software package may require a different gcc version to compile than another package.) You may have come across this when trying to run a python package that requires an earlier version of python.

What is the overall strategy to avoid the dependency nightmare? Where possible, we need a separate software environment for each step of an analysis (another way to look at it is to bundle the software and its dependencies with versions together). When we’re done with one executable in a workflow, we should unload it and then open the next software environment. Here’s a good read about software environments and why you should care.

That said, you have options when you need to run software on rhino/ gizmo. Let’s talk about the order which you should use for finding and running software.

What is a Software Environment?

What is a software environment? A software environment includes the software that you’re running (such as cromwell) and its dependencies that are needed to run (such as certain versions of Java). You’ve already used a software environment on your own machine. It’s a really big one, with lots of dependencies.

For example, on my laptop I installed a Java Software Development Kit (SDK) so I could run Cromwell, and that is one part of the big software environment, including python and R.

The problem comes when another software package needs a different version of the Java SDK. We’d have switch a lot of things around to make it possible to run it.

This is where the idea of isolated software environments can be useful. We can bundle our two different applications with the different Java SDKs. That way, our two different software packages can run without dependency conflicts.

Recommended Order of Execution

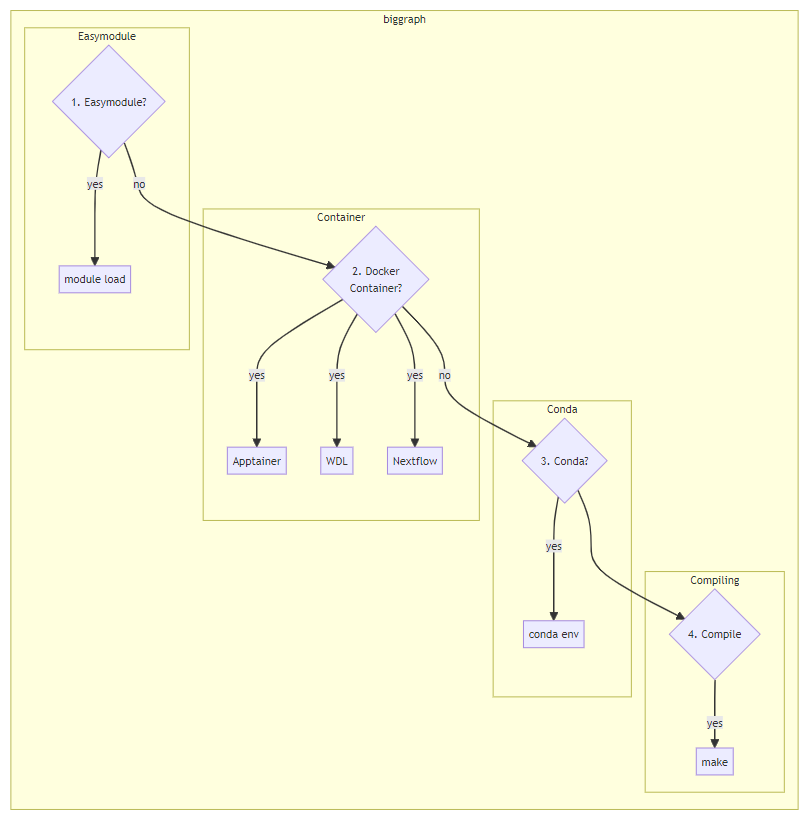

We’ll focus on standalone executables, such as samtools or bwa mem. Click on the links to jump to that section. The order in which you should try to run software:

- Is my software already installed as an environment module? (Look for it using

module avail, such asmodule avail samtools)That is, use themodule loadcommand to load your module, and run it. Why: Scientific Computing spends time optimizing the modules to run well onrhino/gizmo, and they’ve solved the dependency nightmare for you. - If it’s not in an easymodule, is it available as a docker container? Then you can use a) Apptainer commands, b) a Workflow Description Language (WDL) engine, or c) Nextflow to run your software. Why: using containers isolates software environments and is a best practice overall.

- Is my software available via

conda? You’ll install software withconda envandconda install. Why: usingconda envwill isolate your software environments, avoiding the dependency nightmare. - Do I build my package from source? This should be your last resort, because it often requires knowledge of compilers to get it up and running. You will probably be using some variant of

make.

The next section talks about basic best practices when running software using each of these methods.

General Advice

- Before reinventing the wheel, check out the WILDS Docker Repository to see if there’s a similar workflow to what you need. You may just need to fork an existing workflow (make your own version) to get started.

- Avoid mixing and matching your software environments and loading them all at once to avoid dependency conflicts. In practice, this means sticking to either environment modules or Docker containers if possible.

- Pick a version number for your software. This practice will keep your workflow reproducible if the latest version of the software changes. For easymodules, you can see the versions using

module avail <module-name>, such asmodule avail samtools. - For Docker containers, pick a tagged container from the container image library. For example:

biocontainers/samtools:v1.9-4-deb_cv1

1. Best Practices when using environment modules

Finding modules

- Documentation on

lmod(what you use when you domodule loadis here) - Find available modules using either the webpages or

module avail. Find a specific version number (if you don’t know, pick the latest version). For example:module avail samtools

In your script

- The first line should be to load the module script:

source /app/lmod/lmod/init/profile module loadwhen about to use software in your script (use specific version numbers). For example:module load SAMtools/0.1.20-foss-2018b- As a dry run on the command line,

module loadand check to see that you can see the executable usingwhich. For example:which samtoolsshould return the path where this binary is installed (/app/software/SAMtools/0.1.20-foss-2018b/bin/samtools). - Do you work in the script. For example:

samtools view -c myfile_bam > counts.txt module unloadyour module ormodule purgeall modules when done using them and starting a new step. Try not to load all modules all at once at beginning of script. For example:module unload SAMtools/0.1.20-foss-2018b

Here’s an example illustrating this:

#!/bin/bash

module load SAMtools/0.1.20-foss-2018b

samtools view -c $1 > counts.txt

module purge

2. Best Practices When using Containers

One of the best introduction to containers is at the Turing Way. There are three options to run containers: Option 1 can be directly applied in your script, wherea Option 2 requires knowledge of WDL. Option 3 is to use Nextflow to launch your analysis.

Containers Option 1

Run software in separate isolated containers rather than a monolithic environment to avoid dependency nightmares in your bash script

- Load in

apptainerusingmodule load Apptainer/1.1.6(or the latest version.) - Use

apptainer pullto pull a container (note that we recommend using Docker containers). For example,apptainer pull docker://biocontainers/samtools:v1.9-4-deb_cv1 - Use Apptainer to

runa container on your data. For example:apptainer run docker://biocontainers/samtools:v1.9-4-deb_cv1 samtools view -c my_bam_file.bam > counts.txtwill runsamtools viewand count the number of reads in your file.

We recommend using grabnode to grab a gizmo node and test your script in interactive mode (for example: apptainer shell docker://biocontainers/samtools:v1.9-4-deb_cv1). This makes things a lot easier to test the software in the container. If you don’t understand how the software is set up in the container, you can open an interactive shell into the container to test things out.

Here’s an example script:

#!/bin/bash

module load Apptainer/1.1.6

# script assumes you've already pulled the apptainer container with a

# command such as:

# apptainer pull docker://biocontainers/samtools:v1.9-4-deb_cv1

apptainer run docker://biocontainers/samtools:v1.9-4-deb_cv1 samtools view -c my_bam_file.bam > counts.txt

module purge

Containers Option 2

Use Workflow Description Language (WDL) or Nextflow to orchestrate running containers on your data. The execution engine (such as miniWDL, Cromwell, or Nextflow) will handle loading the container as different tasks are run in your WDL script.

There is a graphical user interface to running WDL scripts on your data on gizmo called PROOF.

If you want to learn how to write your own WDL files, then we have the Developing WDL Workflows guide available.

Containers Option 3

Use Nextflow to run your software. Requires knowledge of Nextflow and Nextflow workflows. For more info on running Nextflow at Fred Hutch, check this link out.

3. Best Practices When Using Conda

Starting Out

- Conda documentation is here. If you don’t know where to start, this page by the Turing Way is one of the best resources I can find.

- Use the

Anacondaenvironment module to loadconda. For example,ml Anaconda3/2023.09-0 - Make sure that you’ve updated your conda channels first. To do this, run the following code in your terminal (you only need to do this once, as it creates a configuration file in your home directory).

conda config --add channels bioconda

conda config --add channels conda-forge

conda config --set channel_priority strict

Your `~/.condarc” (conda config) file should look like this:

channels:

- conda-forge

- bioconda

- defaults

channel_priority: strict

Note that some channels (like defaults) require a subscription, but bioconda and conda-forge do not. You can remove the - defaults line to avoid this.

Making a conda environment

- Use

conda createto install your software to the home file system in its own environment. For example:conda create --name samtools_env samtools=1.19.2-1will installsamtoolsinto an environment calledsamtools_env. Try to limit installing more than one utility into each environment to avoid the dependency nightmare.

In Your Script

- Load the

Anacondaenvironment module:ml Anaconda3/2023.09-0 - When using your software, activate your environment using

conda activate. For example:conda activate samtools_env - Make sure that your software is available using

which:which samtools. This should return a path to where yoursamtoolsbinary is installed. - Do your work in your script with the software.

- When you’re done with that step,

conda deactivatethecondaenvironment. For example:conda deactivate.

Here’s an example script, assuming you have installed samtools into an environment called samtools_env:

#!/bin/bash

ml Anaconda3/2023.09-0

conda activate samtools_env

samtools view -c $1 > counts.txt

conda deactivate

module purge

4. Best Practices When Compiling from Source

- Double check to make sure that there isn’t a container or a precompiled binary available. I’m serious. This is going to take a while, and you want to make sure that you are using your time wisely.

- Load the FOSS module, which contains up to date compilers:

ml foss/2023b. - Ask SciComp if it’s possible to make it into a module (they know a lot!)

- Before doing anything: look on Biostars or Stack Overflow to see if there’s compilation advice.

- Compile following the instructions. Be prepared to debug a number of steps.

- Add your compiled binary to your

$PATHin your.bashrcfile - Document everything you did.

What if I Inherited a script or workflow?

Your future self (and future lab mates) will thank you for taking the time to disentangle the code and solve the dependency nightmare once and for all. If you need help, be sure to schedule a Data House Call with the Data Science Lab and Join the Fred Hutch Data Slack and join the #workflow-managers channel.

For community support (you’re not doing this alone!), consider joining the Research Informatics Community Studios.

How can I transform my Bash Script to be more reproducible?

How can we make a script that uses environment modules to be more reproducible? We can isolate the modules by loading them only when we’re using them in a script.

Here’s an example where we are running multiqc and bwa mem on a fasta file.

#!/bin/bash

# usage: bash combo_script1 $1

# where $1 is the path to a FASTA file

# Load relevant modules

module load MultiQC/1.21-foss-2023a-Python-3.11.3

module load BWA/0.7.17-GCCcore-12.2.0

#run multiqc

multiqc $1

#run run bwa-mem

bwa mem -o $1.mem.sam $1 ../reference/hg38.fasta $1

The more isolated software environment approach is we load and unload modules as we use them:

#!/bin/bash

#load multiqc first - first task

module load MultiQC/1.21-foss-2023a-Python-3.11.3

multiqc $1

#remove modules for next step

module purge

#load bwa - second task

module load BWA/0.7.17-GCCcore-12.2.0

bwa -o $1.mem.sam $1 ../reference/hg38.fasta $1

module purge

This also has the advantage of being the first step in transforming your script to WDL. Each of these module load/ module purge sections is basically a task in WDL.

How do I transform a snakemake script to WDL?

This assumes that nothing similar exists in WILDS WDL Workflows. If something does, then fork that workflow and start from there.

- Start with the Bash code: separate each step into its own task. See above example.

- For each task, identify the inputs needed for that task and their formats. This might be an output from a previous task.

- Identify the outputs generated for that task.

- Identify the software needed for that step, and find either:

- A Docker Container with that software (preferred) with a version number

- An environment module with a specific version

- If using Docker containers: In your

runtimeblock, usedocker: mycontainer:version_numberto specify your docker container. Note:latestis not a version number. - If using environment modules: use

module loadandmodule purgein the script block for each task, and make sure to specify a version number.