The Data Science Lifecycle

The Data Science Lifecycle (DSLC) is the conceptual model used to describe a data science process. It describes the iterative steps taken to develop a data science project or data analysis from an idea to results.

An introduction to the DSLC

Different models for the DSLC are used in tech companies, among researchers, and in other industries. For example, CRISP-DM is an open model that has been widely adopted and adapted since it was first published in 1999.

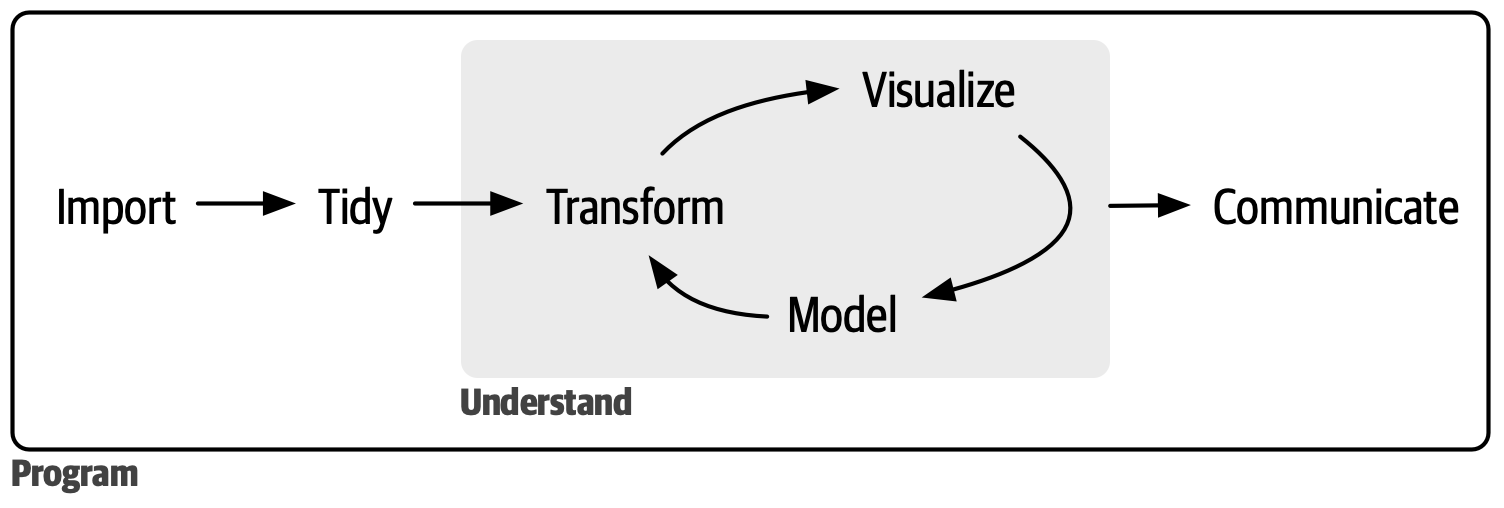

R programmers may be familiar with the model popularized by Hadley Wickham, which is illustrated in the R for Data Science book (Wickham, Çetinkaya-Rundel, and Grolemund; 2023).

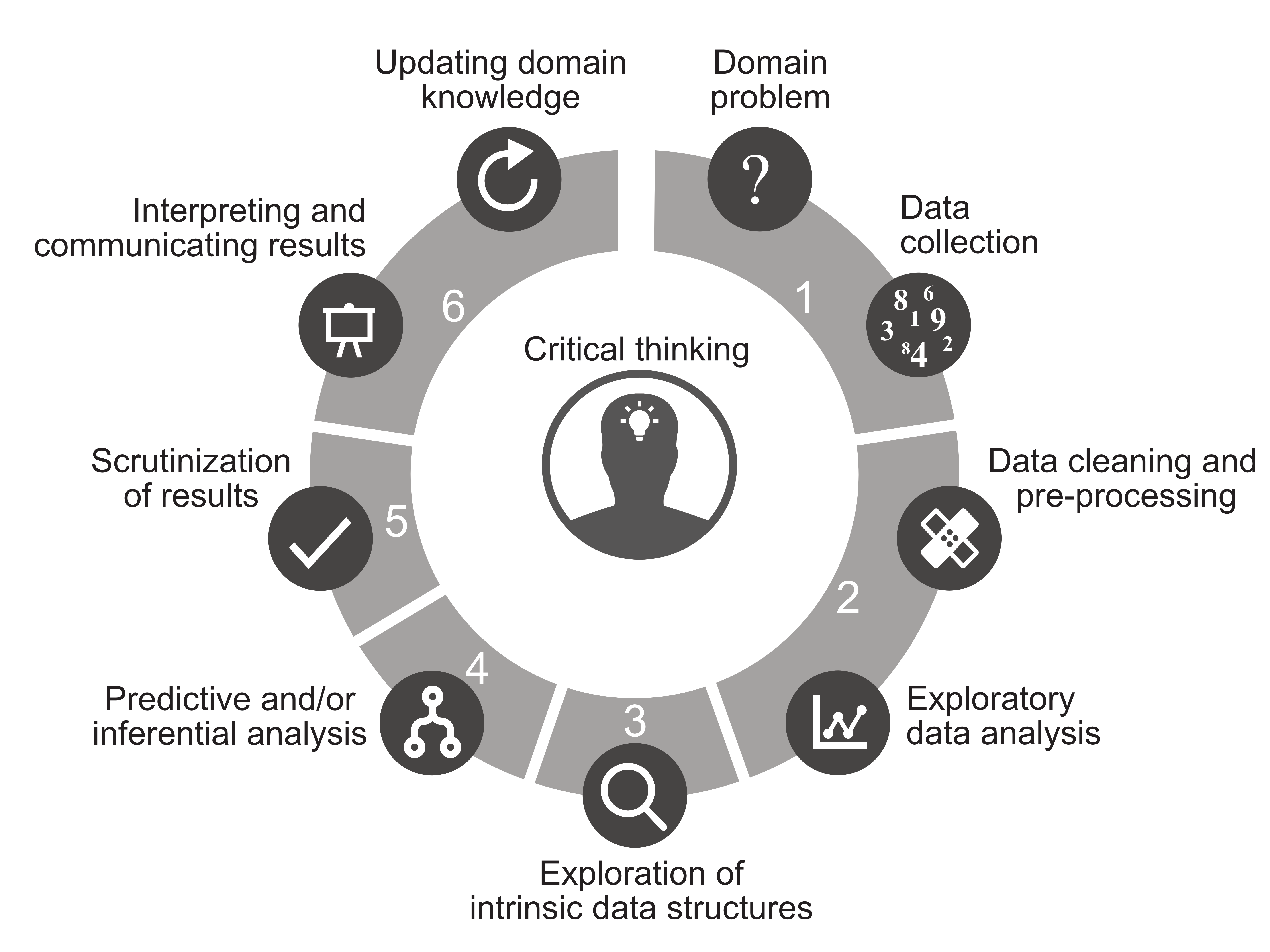

Another model is depicted in Veridical Data Science (Yu and Barter; 2024).

Many research-focused models tend to conclude with the interpretation and communication of results. Other models, such as those developed by Microsoft or the Data Science PM, place more emphasis on the resources and organization needed for deploying and monitoring models in production.

There are many other examples of DSLC models. See “DSLC examples” at the bottom of this article to explore these.

Why the DSLC matters in (biomedical) data science

Biomedical data science often involves diverse teams of contributors, with each person bringing in specialized knowledge and expertise. Laying out a pattern of working allows you to understand if you have the necessary ingredients for a successful project. Whether you’re working on a team of data scientists, or your developing code on your own, defining a lifecycle for your work will help you with:

- understanding the problem at hand and why you should focus on it,

- standardizing projects to make it easier to find information about them,

- building infrastructure and tools for project execution,

- and bringing in cross-team collaborators and external stakeholders throughout the project.

An example DSLC in biomedical data science

We’ll go through an example DSLC designed for a biomedical data science team at Fred Hutch Cancer Center. This example borrows heavily from the Veridical Data Science and the Data Science PM models.

Problem definition and planning

In this phase, we research the problem to be solved and why we should solve it. We engage stakeholders, make a plan, and create buy-in on the data science team.

After an initial project is proposed, more research may be needed to clearly define and scope the project, including consultation with stakeholders or domain experts. Projects are more likely to be successful and impactful if we understand the problem, why it’s important, and the possible challenges before starting. We want to make sure that the project aligns with our team’s goals and that we have the time and resources to execute.

We use repeatable components or templates to standardize this step:

Data preparation & exploratory data analysis

In this phase we acquire, prepare, and document data sets. We check any issues or inconsistencies in the data with visualizations and summaries that are presented to our stakeholders. Each step is documented in a reproducible notebook or script in our project structure.

We begin by using a template repository on GitHub to set up the standardized structure for our project. Within this repo, there are defined folders for data cleaning, pre-processing data, and exploratory data analysis. This structure is outlined in the repository README. In this step, it’s important to present summaries and visualizations to our stakeholders for early feedback and gut checks.

Examples of data science project repo templates:

- dslp-repo-template

- VISC templates

- Research Compendia, The Turing Way

Analysis development

This is where we execute what was outlined in the analysis plan portion of our overall project plan, and these steps will depend on what was outlined there.

It’s important to focus on the “minimum viable model,” or the simplest model/analysis/visualization that solves the problem at hand. We encourage modular, tested code, whether that is in the project repo itself or in a shared code library/package that we use across projects. We build in assertive testing of data and assumptions, which is especially important for projects that ingest new data over time. In this phase and the prior phase, it’s especially important to utilize peer code review and agree on a consistent git branching structure.

Again, remember to present and incorporate feedback from stakeholders!

Distribution

There are many ways of distributing the results of a project and making it available for others. Some projects will be deployed “in production”, while other projects may take a more traditional research route of communication and dissemination. A deployed project is one that will continue to be used, often with updated data or interactive elements, over time — for example, a dashboard or a predictive model applied in the clinic. Other projects result in static outputs, like a manuscript. How will you make sure your project/analysis is findable–for future us, in the organization, or on the wider internet? How will you make sure that it will continue to run (or be reproduced) over time?

DataOps

After a project is deployed, we must consider the work and resources needed to maintain the model/dashboard/etc., and that information about the project continues to be discoverable by the appropriate audience.

What work and resources are necessary to monitor a project?

- Code base

- Changing data

- Model performance

- Data governance over time and user permissions

This DSLC isn’t intended to be a strictly linear process. Iterations may occur and you’ll need to circle back to previous steps. However, it’s necessary to document your intended path in the data planning stage so that if project resources, goals, or deliverables change over time, these changes are visable and agreed on.

Resources

- Veridical Data Science

- Software Engineering for Data Scientists (Arnold Library access) by Catherine Nelson

- Opinionated Analysis Development

- Machine Learning in Production: From Models to Products

DSLC examples

- The Data Science PM, The Data Science Life Cycle

- Joe Blitzstein and Hanspeter Pfister, The Data Science Process

- Philip Guo, The Data Science Workflow

- Hilary Mason and Chris Wiggins, A Taxonomy of Data Science

- Roger D. Peng and Elizabeth Matsui, The Epicycles of Analysis

- Open a pull request on this page to add yours!